Transylvania

Erdély – Siebenbürgen – Ardeal

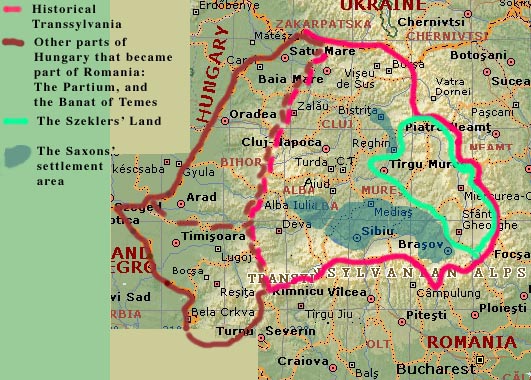

The name of Transylvania was first mentioned in the 11th century for a territory then under the Hungarian crown. This historical Transylvania started at the King’s Pass (Pasul Craiului), the most important pass leading there from the west, on the street between Nagyvárad (Oradea) and Kolozsvár (Cluj). Historical Transylvania is bordered by some lower mountain ranges in the west, and enclosed by the Carpathians from north, east and south.

Later, after new borders were drawn after the peace treaty of Trianon it became common to refer to all these former Hungarian, now Romanian territories as "Transylvania". The other two entities, called the "Partium"– the area between Satu Mare and Arad –, and the "Banat of Temes" with its centre Temesvár (Timişoara), geographically belong to the Great Hungarian Plain and differ very much from original Transylvania in landscape, climate, customs and culture.

Map of Transylvania

Transylvania occupies a controversial place in the national consciousness of both Romanians and Hungarians. To both of them it is like a cradle, a centre of cultural heritage, and its name is entangled in strange ideas about national identity and continuation.

The Romanians claim that they are descendents of the Dacians, and the Romans that came to Transylvania after the Roman conquest under Traian (101-106 a.d.).

The Hungarian historiography maintains that they wandered to Transylvania from the Balkans after the dissolution of the Roman Empire, and especially upon the pressure of the Turks. The Hungarians claim the Romanians came there after the Hungarians’ migration and their "Taking of the Land", as they call their conquest of the territories of the Great Hungarian Plain and Transylvania where they settled.

It is acknowledged that some Slavs were living there when the Hungarians came, but the Hungarian historiography is quite ignorant or perhaps discreet about who was really there and whether they gave them a warm welcome or put up a fight. What happened to all the other peoples that had lived in or passed through Transylvania before, the Gepids, the Goths, the Huns, the Avars? And the Dacians? Had they all vanished without a trace?

Due to the lack of sources during the time of the Migration of Peoples (4th to 6th century a.d.) and later, and perhaps also due to a rather selective way of investigation from the scholars involved in both Romania and Hungary, none of these migration theories has been proven, and none has been refuted, either.

It sometimes seems not a scientific question, but a rather childish quarrel about who came there first, and should therefore have the rights of the landlord.

|

Heating in Transylvania

|

Medieval Transylvania occupied a particular place within first the tribal realm, then the kingdom of Hungary. It was for a long time ruled by a special Voivode or War leader. Transylvania, a kind of natural fortress because of the Carpathian mountain ranges, had to protect the Hungarian Plain from the East. Due to the different geography and climate, and also the settlement policy, the inhabitants of Transylvania developed skills, agricultural methods and habits very different from those on the plain.

When the Hungarian kingdom collapsed after the battle of Mohács in 1526 and finally after the Turkish conquest of Buda in 1541, the Hungarian statehood continued in the Principality of Transylvania. While all of Europe was stricken in religious wars, in Transylvania relative tolerance ruled. The principality was spared from the 30-years War.

At the same time it was exposed to incursions of the Turkish troops or the Voivodes of Moldavia and Wallachia, who were sometimes called in by the Transylvanian princes themselves. The greatest destructions and slaughters, though, were performed by Hapsburg troops during the 15-years war (1591-1606).

Hungarian historiography maintains that Transylvania was the last, most eastern stronghold of Christianity. This perspective of course is tendentious, if not to say wrong. It was the Turks that helped maintain independent Transylvania, protecting it from Habsburg conquest for one and a half century, because they wanted a buffer zone between the Ottoman and the Habsburg Empires.

The above mentioned perspective also neglects the fact that the Danube principalities – Moldavia and Wallachia – were also Christian, and preserved their faith and national identity with the help of a great number of monasteries.

It does have some background, though, in the field of architecture: The most eastern monuments of Gothic and Renaissance style are to be found in Transylvania.

|

|

The castle of the Counts Lázár

in Szárhegy (Lăzarea), where the Transylvanian prince

Gábor Bethlen was raised, being a relative of them ...

... and the Bethlen family castle in Kereszt (Criş), ...

... both rather rundown in the course of time, and in a state of constant renovation for the last 10 years.

|

While Transylvania was a principality, the southern and central part of Hungary, including such important towns as Buda, the capital, or Esztergom – before and afterwards the seat of the archbishop –, were under Turkish rule, while Western Hungary and what is today Slowakia belonged to the Habsburg Empire.

The eastern part of the Great Hungarian Plain frequently changed its owner, and therefore came to be known as "Parts", either of the Hungarian kingdom or of Transylvania, or in awkward Latin, the "Partium".

When the Ottoman Empire finally weakened and the Turks were driven out of Hungary by the Austrian troops (with the help of some German princes) at the end of the 17th century, Transylvania remained on its own. Many people in Hungary didn’t want to accept Habsburg rule because of its violent attempts of reconversion. These resistance fighters came to be known as "Kuruc" people, and supported the pretenders to the throne, the last of whom, Ferenc Rákóczi, was deserted by his noble followers in the treaty of Szatmár – that granted certain rights to maintain their religion to all confessions – and was forced to spend the rest of his life in exile in Turkey.

|

Torockó

Still, for a while it was connected with it, or pawned to them, therefore it entered the book of Orbán. He writes that the settlement was mentioned in a document from 1291, from which it can be guessed that it was founded a lot earlier, before the Mongolian invasion, probably at the same time the nearby settlements of Torda (Turda) and Kolozsvár (Cluj) were populated with German settlers. According to this document the first inhabitants of Torockó came from Austria, and Orbán believes they might have come from the town of Eisenerz in Styria.

Still, the houses are well-kept, so I assume they have all been turned into weekend houses for better-off people from Turda, Cluj, or Gyéres (Cîmpia Turzii). Orbán also writes that in his days (around 1880) it was the only village in all of Transylvania without a pub – and this also hasn’t changed till today. So, a nice place, and situated in a nice area, but sparsely inhabitated, – and without a pub: this is as Torockó presents itself nowadays. |

After the treaty of Szatmár (Satu Mare) in 1711 the Austrian rulers did everything to prevent the lands of the Hungarian Crown to form a unity again – and perhaps have the Hungarians again rise against them. So they ruled Transylvania separately, and attached the Partium to it. Hungary proper was ruled by a Viceroy and the Table of the Seven Persons in Buda, with a right to legislate for the Diet at Pozsony (Bratislava). Transylvania was ruled by a various authorities: a military one, a chancellor and chamber elected in Vienna, a Governor, and also a Diet. Most things, though, were decided in Vienna.

It was in the 18th century that Transylvania started to stagnate in its economical development. Even in the 19th no industry worth mentioning emerged in Transylvania. One should not see only the disadvantages of such a development. Still today in many ways it is like a museum for methods and skills long forgotten in other parts of the world. And despite its sometimes rather turbulent history it has preserved a great amount of historical monuments from many centuries, many of which are still used today.

|

Fogaras Fortress The origins of the town of Fogaras (Făgăraş) supposedly date back to the Hungarian conquest of Transylvania. Later Saxons also came to live here, but already very early it became a predominantly Romanian settlement.

– in relation to almost 79.000 Romanians. Before World War I it served as a garrison, and later as a prison. My impression upon visiting it was that is now used by the town’s administration, for offices, and perhaps storage. |

A source of constant controversy between professional and amateur historians (that is almost everybody) of both ethnicities is the time and numbers when the Romanians started to arrive. No doubt exists about the fact that there was a constant migration from Moldavia and Wallachia since the 13th century. But little is known about those who were there or came before. Some of those who came from across the Carpathians for a long time lived in remote areas, didn’t have a classification as serfs, didn’t pay any duties and didn’t enter in any documents. Others came as settlers, called in by Hungarian authorities, led by "kenez" (from the Slavic word "knyaz", leader) and settled in areas that were assigned to them. These Romanian leaders lost their noble status with the Decree of Turda in 1366 if they didn’t convert to Catholicism. This was a measure taken by the then king of both Hungary and Poland, Louis the Great, to show his compromise towards Rome and support the pope in his fight against the Eastern church. The Romanian nobles were not included in the "Union of the 3 Nations", formed in 1437. This left the Romanians without political representation for the centuries to come.

But still, some of them entered into the Hungarian nobility, and – a fact not mentioned frequently in Hungarian historiography – the father of their great king Mátyás (Corvinus), János Hunyadi, was of Romanian descent. The Romanians therefore claim Mátyás, too, as theirs: They call them Iancu de Hunedoara and Matei Corvin.

|

The house in Kolozsvár (Cluj) where king Mátyás (Corvinus) was born, the most venerated of all Hungarian kings.

Cluj, that started as a German settlement, came to be the cultural centre and later the capital of Transylvania. For almost 2 centuries it was the most important Hungarian city after Budapest. And even after becoming part of Romania for quite a while it still preserved its Hungarian majority and cultural importance. Still, the Romanians also claim it as their heritage, mostly for its Roman origins and not for its medieval and later role. Now it is the second largest city of Romania, an important university centre and the big rival of Bucharest in culture and science, – and real estate prices. |

When Transylvania came under Habsburg rule the Romanians received special attention by the authorities. First, their national consciousness was encouraged in order to weaken the Hungarians. Second, in order to weaken the influence of Russia on their orthodox subjects, the Habsburgs strongly supported, one may almost say founded the Romanian Greek Catholic Church.

In the course of the split between the Western and Eastern Christianity, and the wars between local leaders and against the Turks, many communities might have their spiritual leaders and some kind of religious beliefs and practice, but no idea which ecclesiastic authority was in the end in charge of them: Constantinople, or Kiev, or a local bishop in the next town? This uncertainty was exploited by the Habsburg rulers, the most faithful allies of the Holy See, and they did everything in the countries they conquered to persuade as many orthodox followers as possible to join the "unified" churches whose highest authority was the pope in Rome.

The centre of the Romanian Greek Catholics was the village-town of Blaj, and it became the spiritual cradle of the idea of a Romanian Nation. Under the influence of this church from 1800 onwards emerged the representatives of the "Transylvanian School" (Școala Ardealană) who fought for political, religious and legal equality and developed and popularized the idea of the Daco-Roman descent of the Romanians.

|

The entrance tower of the (Orthodox) cathedral in the castle quarter of Alba Iulia, built in 1922 – the copy of a Wallachian church in one of the old Voivode’s residences, either Tîrgovişte or Curtea de Argeş. It was built in Alba Iulia as a sign that because of its role in the creation of Great Romania this is a city of true Romanian spirit and heritage. |

|

The first bible in Romanian was edited in Transylvania. (In the Orthodox churches and monasteries until then they still used the Old Church Slavonic Language.) Due to the influence of the Greek Catholic church the Romanian language changed from the Cyrillic to the Latin script. And it was in the town of Alba Iulia – the provincial capital to which Blaj belongs – where the unification of the Romanian lands was declared in 1918.

The members of this religious confession – which played such a prominent role in Romanian history – in communist Romania were treated as traitors because of their adherence to Rome. Their priests were arrested or worked in illegality, their churches and other property was confiscated, and given to the Romanian Orthodox church. The Greek Catholics have been fighting since 1989 for restitution, but their case still hasn’t been resolved. The expropriation decree has been revoked, but both local and Orthodox church authorities have been reluctant to restitute.

|

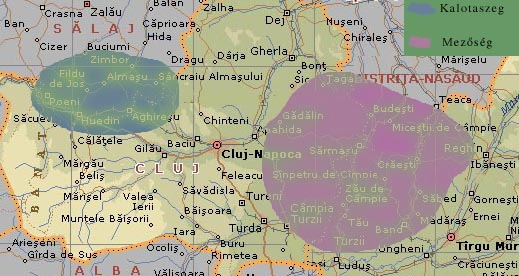

Kalotaszeg and Mezőség Transylvania has still more landscapes and places which are for one or another reason dear to the Hungarians.

In the town of Bánffyhunyad (Huedin) and in many villages of the Kalotaszeg the traveller can admire two- or three-story-houses with arcades, towers and shining aluminium roofs, and portals with resting lions (in common parlance: Gypsy palaces) that evidently are a result of this sucessful business.

The series of CDs with these songs and dances is called "Last Hour". (The last preservers of this heritage are mainly Gypsy professional musicians.) I once picked up a hitchhiker in the Mezőség who complained to me that he would like to make rock music but the equipment was so expensive, and in order to stage a concert somewhere you need a car, even a truck, and then you need high voltage current which most inns don’t have, and life is therefore really difficult here in the Mezőség! When I told him to get a fiddle or an accordeon and just play unplugged, he was offended ...

This typical Mezőség house shows that people aren’t breaking their backs in taking care of their house, garden and fence, but still live in stable conditions. |

Perhaps one ought to mention two minorities of Transylvania which for various reasons aren’t that frequently object of attention: The Gypsies and the Jews.

The Jews came to Transylvania from both sides. From the West they came to Hungary mostly from Moravia and settled as "protected Jews" of one or the other Hungarian nobleman who gave them permission to settle on his estates, benefitting from this financially. They payed taxes to him, and they lent him money, usually forever, as they were dependent on his protection.

From the East they came pouring in slowly from Russia and through the Danube Voivodships, as wandering merchants, first only keeping storage places, and selling on occasional markets, then opening shops, and finally settling down when they were allowed to by the municipial or county authorities.

Somehow it seems that they never managed to have produced important intellectual or cultural personalities. Apart from their commercial activities they contributed a lot to social life, donating money for the funding of schools, orphanages, free kitchens to the poor. The most remarkable member of their community was Béla Kun, the founder of the Hungarian Communist party and the short-lived Hungarian Republic of Councils in 1919, who later perished in the Soviet purges of the 1930s. He came from the Szilágyság (Sălaj), a border region of historical Transylvania and the Partium, and for a while lived and worked as a journalist in Cluj. He fought in the Austro-Hungarian army in World War I, and as a prisoner of war in Russia he became an adherent of Bolshevik ideology. Nobody likes to remember him, and nobody claims him as theirs, neither in Transylvania nor in Hungary, neither the non-Jews nor the Jews.

|

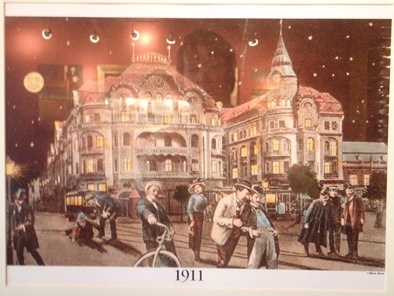

Nagyvárad The city of Nagyvárad (Oradea) is a typical town of the Great Hungarian Plain, and the centre of the Partium. A traveller who went from Debrecen to Várad in the 19th century complained about the lack of sensations on the trajectory: "A very boring landscape. The highest elevation in it is an ox." Várad id situated on a river, the Sebes (=quick) Kőrös (Crișul Repede), and was an important crossroads for traderoutes. To this fact it owned a certain prosperity in the 19th century which has left its mark in a lot of Art Noveau buildings in the centre. At the turn of the 19th to the 20th century it also had great cultural importance for Hungary: Here a review was edited that for about two decades served as a light tower to the Hungarian intellectuals: the "West".

After the treaty of Trianon the importance of Várad waned. It lost its transmitting role between Transylvania and the Great Plain. It never has been a town of special importance to the Romanians. It housed, though, an important Jewish community: It was the largest one of all those which came to form part of the Romanian State after Trianon. There is still a synagogue in Várad, and a Jewish community, but the overwhelming majority of the Jews from Várad perished in the Holocaust. Várad even turned into a centre of deportation for the Transylvanian Jews in 1944, having the biggest ghetto after the one in Budapest.

Várad had some important industries till 1989, but most of them closed down. It is an important school city, also for the Hungarians. There is even a German speaking community there, most of them descendants of Swabians. It seems to me that slowly Várad is regaining its role as the entrance gate to Transylvania.

|

The Gypsies came to Hungary in the 15th century from the Balkans, as a result of the Turkish raids and conquests. Hungary was one of the few, perhaps the only country which somehow welcomed them. The Hungarian kings and nobles settled and integrated them, as they appreciated their skills in working metals. They were welcome also as a force against the disobediant serfs, and allegedly they played a sad role in the repressions against the great serf uprising in 1514.

The persecution of the Hungarian Gypsies only started when the Habsburgs took over Hungary at the end of the 17th century. Their language was forbidden, their kids taken away, they were fobidden to exercise their profession, and many were driven out of their homes. The persecution of the Gypsies was a part of the Habsburg strategy of weaking the Hungarian nobles who gave shelter to the Gypsies on their estates and gained income as they profited from their skills as locksmiths and coppersmiths.

The Gypsies also fled to Wallachia and Moldavia from the Balkans, also in the 15th to 16th centuries. Some of them also came from Armenia, for similiar reasons. The medieval Danube Voivodships, though, gave them a far less warm welcome than the Hungarian kings: They were considered intruders and troublemakers and cast into slavery. They were kept and traded as slaves till the middle of the 19th century. It was only after the unification of Wallachia and Moldavia under Alexandru Ioan Cuza that the slavery of the Gypsies was abolished.

As a result of their finally regained freedom the Wallachian and Moldovian Gypsies immediately started to travel, evidently giving way to a deep-rooted desire to know the world. They naturally came to Transylvania and other parts of Hungary first, and after some wanderings many of them decided to settle here.

In most of Romania these "Wallachian Gypsies" prevail, while the Hungarian Gypsies or "Romungros" have assimilated or vanished. They dress traditionally, the women in long colourful skirts and headkerchiefs, the men in dark suits and black hats. Many of them are small merchants, going from one market to the next, trading with everything possible. Some of them work as locksmiths or panel-beaters in rural Transylvania: if someone needs a new tin roof or gutter he calls the "Gypsy".

|

In the rather small

village of Betfalva (Beteşti), near Székelykeresztúr

(Cristuru Secuiesc) there are two families or clans of Gypsies: the

well-to-do ones who live in the best-equipped houses and make their

living on producing wickerwork and brooms which they sell on the regional

markets; and the "carcass collectors" who live on almost

nothing, in miserable huts or even "putri-s" (dwellings

dug into the earth and covered with a roof of branches with plastic

sheets on top), and die young. |

Many of the Gypsies also work as professional musicians, playing at village feasts and weddings. Among them and the merchants are quite wealthy people. Those on the other scale of the social spectrum beg in the streets, steal and sell their children. Still the Romanian Gypsies do have some kind of overall organisation and elect a leader, a king or "Vajda". According to someone who knows the issue better than I do there are at least 3 of them at present. There are also charity and human rights’ organisations fighting against discrimination.

When Austria in 1990 introduced visa for Romanian citizens some Bucharest journalist made up a hoax: This was only because some Romanian Gypsies had eaten a swan in Vienna’s City Park! This story was eagerly believed by most Romanian citizens, and spread further on. For years the Romanian Gypsy communities staged protests to have this nonsense officially denied.

|

The castle of Zsibó (Jibou), once in the possession of the Counts Wesselényi. Now it belongs to the community. Inside there are offices and a place for festivities. In the back yard there is a circuit for people learning how to drive a car. On the other side of the park there is a glass house with jungle plants. The whole place is in a rather bad state. |

|

Though once a Hungarian settlement, it was exactly the local nobles who in former times attracted the Romanian peasants, in the place of Hungarian ones who ran away, or weren’t content with the conditions offered. Now in Zsibó few Hungarians have remained, and most people – who evidently have moved to the town only in recent times – don’t even know there is a castle ...

The most famous of the Wesselényis was Miklós, who in the 1830s was a friend of the two most profiled Hungarian reform politicians, István Széchenyi and Lajos Kossuth. Later, as he lost his sight he gave up politics and went back to Zsibó.

In 1848 he travelled up to Budapest to implore his old friend Kossuth to abstain from his nationalist demands, fearing a confrontation between Romanians and Hungarians in Transylvania (which then in fact took place), but his pleas were igored by Kossuth. Wesselényi fled from Hungary to Moravia as fighting started, and on his way back home he died in Pest in 1850, a few months after the supression of the War for Independence.