|

The

Szeklers’ Land

The Szeklers’ origin is disputed.

The chronicle of a Byzantian emperor, – "Purple-born Constantine"

–, suggests them as a people apart from the Hungarians, eventually

descendants of the Khazars. As the son of Attila held court in the town

of Székelyudvárhely ("Szekler’s courtplace")

some people have raised the theory that they are descendants of the

Huns. The Romanian historiography maintains that they are Hungarized

Romanians or Turkic people.

|

The Szeklers are renowned in

both Romania and Hungary for their skills in working the wood.

One of the specialities of the Szeklers’ architecture are

the gates of the courtyards, the "Szeklers’ Gates".

|

|

The Szeklers themselves are convinced that

they are Hungarians who have preserved their national identity more

purely than the Hungarians living in nowadays Hungary. Even before the

Szeklers’ Land came to form part of Romania the Hungarians from

outside their territory were referred to as "the Hungarians"

with a certain disdain and distrust. In the Transylvanian Diet they

had an own representation, apart from the one of the Hungarians.

The Szeklers have preserved a "notched

script" from the times they arrived in the Carpathians. (It may

be called Runic for its resemblace to the Nordic Runes, but all sources

I found agree that there is no relation between the two.) Allegedly

in Hungary proper a similiar script existed but when the first Hungarian

king, Stephen, introduced the Latin script the former was forbidden

and only was preserved in the Szeklers’ lands. So we know that

the Szeklers came to the place they chose as their home as literate

people. For the (other?) Hungarians this is less certain.

|

|

|

I have modified the order of the letters,

adjusting it to our habits. The "notch script" originally

was read from the right to the left.

|

The Szeklers were given special privileges

by the early Hungarian leaders and kings to perform the task given to

them: to defend the Hungarian territory against other invaders from

the East. These "privileges" were perhaps merely the codification

of their own laws and customs that the Hungarian leaders could not or

didn’t want to dispute at the early stage of settlement. Besides

these rights they had also the obligation to send soldiers whenever

the Hungarian king of the Voivode of Transylvania would demand it.

| The valley of the river Maros near the town of

Maroshévíz (Topliţa) |

|

A characteristic feature of the Szeklers’

social organization is the prevalence of public property. The woods

and pastures were held in common, the shepherds took care of the whole

village’s cattle, sheep, and so on. Many of these features still

persist today.

Also, among the the Szeklers the women

had similiar rights in holding property as the men, and the sexes were

treated equally in questions of inheritance – perhaps something

they preserved from the times of their migrations from the eastern steppes.

In order to stress the difficult relations

to their Hungarian "brothers and sisters" once again: In Hungary

a lot of evidence with respect to their origins, their original customs,

faith, skills, knowledge and achievements was destroyed after the ascent

of Saint István (Stephen) to the throne. It is more than probable

that the Szeklers, with their fierce resistance to this modernization,

preserved evidence that has been lost in Hungary itself.

|

On Saint George’s day the village shepherds come to every

peasant and collect the sheep in order to take them to the "estena",

the summer pasture.

Betfalva (Betesţi)

|

When István, the first Hungarian

leader who had himself crowned king, introduced Christianity and serfdom

to his compatriots with considerable violence, he met with the fiercest

resistance among the Szeklers. In a rather remote area between Tusnád

and Kézdivásárhely (Tîrgu Secuiesc) lie the

ruins of a castle called the "castle of the idolaters" which

was the last stronghold of the enemies of István’s reform

package.

| On top of this hill are the rather meagre ruins

that remain from Bálványosvár, the "Idolaters’

castle" |

|

The history of the Szeklers from then on

is a history of resistance against serfdom. The Hungarian rulers and

lords of the land tried to impose it with all means, the Szeklers resisted

and staged rebellion after rebellion.

The leader of the greatest peasant rebellion

of Hungary in 1514 was a Szekler: György Dózsa, from Dálnok

(Dalnic) – in nowadays Kovasna county, or more traditionally: Háromszék,

the "Three Chairs". He was an officer from the Turkish wars,

and when there was a call for another cruisade against the "infidels"

a lot of peasants gathered together near Pest. Talking to each other

came to the conclusion that their worst enemy wasn’t the Turks’

threat, but their own lords. They chose György Dozsa as their leader

and the peasant revolt they staged became the most fierce and threatening

in Hungarian history. It was crushed, and Dózsa himself was executed

in an extraordinary cruel manner.

|

The Bucin saddle in the Hargita mountains. |

|

The rather remote village of Varság

(Vărşag) that developed out of the former summer pastures

of Székelyudvárhely (Odorheiu Secuiesc).

|

|

| |

|

Note the yellow, sand-like hills at the right of the above

picture: They are heaps of wood shavings, produced in great quantities

by the carpenters and cabinet makers of Varság, difficult

to get rid of.

A brook in Varság

|

(Only as an appendix: the Hungarian nobles

were then so busy in crushing the peasants’ revolt, in making sure

those serfs would be deprived of any possibility to rise again against

their masters that they had no other thing in mind than ensuring their

dominion upon their serfs, and codifying it. Immediately after their

victory in the peasants’ revolt the "Tripartitum" or

"Book of three parts" was edited, for centuries saving the

Hungarian nobles’ rights against the serfs. Only 12 years later

the Hungarian Kingdom was destroyed by the Turks, as the Hungarian nobles

among themselves weren’t united, and didn’t support the last

Hungarian king – Lajos, killed at Mohács – properly.)

So, as can be stated, there was unity against

their subjects, but no unity against threats from other, alien powers.

The Hungarian subject, or serf, was a more serious enemy to the Hungarian

noble, than the Ottoman Janissary and Spahi ...)

| Fog like this is quite frequent in the basins of

Csík and Gyergyó, due to the waters of the rivers

Maros and Olt crossing them. |

|

The Szeklers were renown fighters and so

the Hungarian, Transylvanian and Habsburg rulers always followed a similiar

policy: Whenever they needed an army they promised to the Szeklers to

grant them their old privileges again and to free them from serfdom.

Once the Szeklers had fought for them and the war had been won, they

were denied their rights. So they revolted, and their revolt was crushed.

So did it happen in the "Bloody Carnival"

of 1596, and these revolts and repressions went on through the whole

17th century, and did not cease after Transylvania was incorporated

into the Austrian Empire with the treaty of Szatmár in 1711.

In the first decades of the 18th century

the Austrian authorities decided to make this

area a part of the Frontier Territory which meant that it was placed

under the direct rule of Vienna and the military authority, the Court’s

War Council. When they started to draft the Szeklers forcibly into the

newly established frontier regiments and those protested and refused,

in 1764 Austrian troops entered by night into the village of Madéfalva

(Siculeni) and killed about 200 of its inhabitants. This was the last

big slaughter of Szeklers, and is remembered as the Terror of Madéfalva,

or in latin: Siculicidium. Today there is a monument in the village

remembering these mass killings.

|

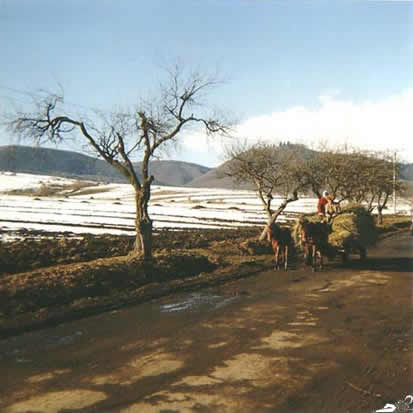

As many people keep cattle, sheep or goats, the production

and storage of hay claims an important place in the agricultural

sector. The hay is often stored in the place where it has been

cut, in small wooden cabins, as the farmhouse itself doesn’t

have enough space to store it there.

Also quite common in the Szeklers’ Land is the employment

of horses in transport and agriculture.

|

The persecution they were exposed to, and

their unwillingness to resign to their fate in the course of time prompted

many Szeklers to flee across the ridge of the Carpathians, the border

of Hungary, into Moldavia and settle there. They mixed with the Hungarian

speaking minority in Moldavia, the Csángós, who

nowadays have been rediscovered by Hungarian politicians both in Hungary

and in Romania, and are subject of controversy regarding their numbers,

their national identity, their command of the Hungarian language, and

most of all: their Catholic faith, often the only thing that still distinguishes

them from their Romanian neighbours.

The Catholic church plays a prominent role

in this controversy, trying to fortify its position as a political force,

and gaining territory in the field of education.

These interferences do not really make

the Romanian government happy, and cause a lot of tension also between

ordinary citizens of Romanian ethnicity, with respect to their Hungarian

compatriots.

|

Traffic is an extremely interesting thing in the Szeklers’

Land. It is both amazing to watch what

is being transported, and how it

is done.

This man brings the wreck of a Dacia to a workshop

where another wreck is awaiting it. They were then both cut apart

in the middle and welded together and so an entire Dacia was made

out of the two wrecked ones.

|

|

|

The wreck, by the way, came by train from another

town, where the workshop had ordered it.

This Dacia car is taking a lot of wool somewhere.

|

During the communist times the Szeklers

for a while enjoyed a certain autonomy, but later they were deprived

of it. Collectivization became very important for the central authorities

in this area, as a tool to further centralization. It wasn’t only

the private land that was especially targetted, but also in a very prominent

place the common grounds of the Szeklers: the pastures and woods.

By collectivizing the pastures they could be taken out of the hands

of the local authorities, and as a part of the collective farms were

placed under the command of a central authority. The woods were nationalized.

So two kinds of public property clashed,

to the detriment of the traditional one.

When someone wanted to keep animals, he

had to cut the grass for them in his spare time, on grounds that were

formerly his own or belonged to the village, and to deliver half or

two thirds of it to the Kolkhose. Only the part that was left to him

he could feed to his cow(s) or sheep. And still, as a friend told me,

then all the grass in the village and on the slopes was cut, not a single

meadow was left fallow – on the contrary to now.

Villages with Romanian population, by the

way, were sometimes spared from collectivization, although their lands

would have offered better conditions for large-scale cultivation than

remote (Hungarian-populated) mountain villages. This has to be mentioned

in order to show that collectivization in Romania often had more political

than economical aims.

|

Meadows and fields near the town of Ditró

(Ditrău) in the basin of Gyergyó.

All the work here is still done by hand, eventually

with the help of horses, or, more seldom, oxen.

Only in the last years tractors have appeared.

|

|

Fields and a typical carved wooden stele in

Háromszék, near the town of Kézdivásárhely

(Tîrgu Secuiesc).

The softness of the landscape is confusing, it is in contrast

to the harsh climate and living conditions that prevail in the

Szeklers’ Land.

|

|

After 1989 these collectivized lands were

restituted in a complicated process that created a lot of work and good

income for lawyers and judges. In the meantime the lands which had no

owner became a prey for clever and unscrupulous businessmen who exploited

them with almost 100% profit, with no investments.

This affected most of all the nationalized

woods. The woods of the Szeklers’ Land have been exploited to the

utmost for about ten years. Many woods only survived because they were

situated in areas that were extremely difficult to access. The

special lorries that carry the tree trunks, called "remorcas"

(= tow-cars) destroyed the roads.

Only in the last years, after restoring

the common property, the wild destruction of the woods has stopped and

a process of reforestation has started.

|

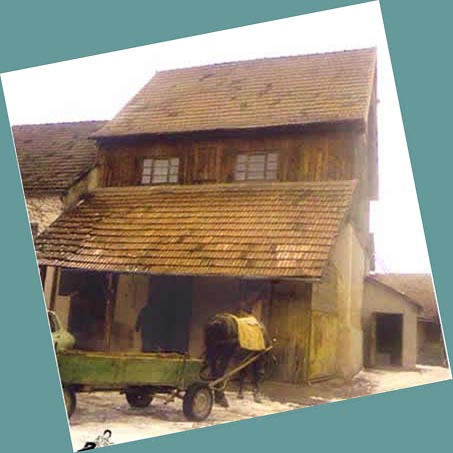

A mill in a village near Székelykeresztúr (Cristuru

Secuiesc).

The machines that grind the grain were manufactured in the

time of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, that is before World War

I, in the Budapest-based Ganz factory that has vanished only in

the 90-ies, due to the privatization process.

The farmers bring the grain and pay with a part of their harvest,

getting back the remainder as flour. No cash is involved.

|

This uncontrolled exploitation of the woods

didn’t take place only in the Szeklers’ Land, but in all of

Romania, and has been the main cause of the floods that have affected

Romania, Ukraine, Hungary and Serbia during the last ten years.

The Szeklers’ Land is not only the

origin of some of the tributaries of the Tisza and Danube, but also

full of natural springs and mineral water, and a lot of spas. As most

other touristic facilities all over Romania, they fell into decay after

the communist era recreation facilities were deserted, as the organisations

owning them – trade unions, schools, pensioners’ organizations

– dissolved, or were left without funds.

Slowly now private tourism on small scale

is emerging and perhaps such spas as Tusnád, Homorod, Borszék

(Borsec) or Hévíz (Topliţa) will one day again live

up to their former glory and prosperity.

|

Tusnádfürdő (Băile Tuşnad)

in rather inhospitable weather.

The heavy fog left the trees clad in a coat of hoarfrost.

|

|

After 1989 lots of factories were closed,

and many people were left without jobs. Some of them managed to retire

at an early age. Many people I know go to work in Hungary, mostly illegally,

in construction.

Many of the youngers don’t want to

bother with working abroad (as they have no skills for that) or with

agriculture (for which they have neither energy nor sympathy), they

would like to make quick money with all means. The latest fashion for

good-for-nothings is to join the French Foreign Legion.

Bad perspectives for the future of the

Szeklers’ Land ...

|

Some more specimen of the architecture of

the Szeklers:

A private house in the village of Parajd (Praid) at the foot

of the Hargita mountains.

|

| The castle of Marosvécs (Brîncoveneşti)

in the valley of the Maros, now an insane asylum. |

|

The Szeklers’ Land has always been

a country of emigration. People emigrated to Budapest, to Germany, to

the United States, to Canada. Some made a good living there, others

failed.

But as a friend of mine said: as far as

I can judge it, in the end they all come back home to die ...

back to Transylvania

back to main

page |