|

The main road of the Altai region: Chuiskii Trakt

The Altai is in the very center of Asia and has an extremely continental climate: In winter the temperature can sink below -40º C and in summer it may rise to +40º C. The region is fertile, and about 15 years ago it was self-sufficent in terms of agricultural products and could even provide the neighboring regions with foodstuff. Now agricultural production is down, the ground is not being tilled any more, cattle is being kept for personal supply only and theft of cattle is frequent. The Altai is sparsely inhabitated. The

main road is the Chuiskii Trakt that leads through the whole republic

until the Mongolian border. Apart from this "magistral" there

are some mayor and minor roads, leading to villages off the Chuiskii

Trakt and to the Uimon valley. Many smaller villages can only be reached

on dirt tracks. In Soviet times helicopters were used to supply the

more remote areas, but this has ceased, the heliports are out of function

and in ruins.

The Chuiskii Trakt leads from the capital

of the region, Gorno Altaisk, to Mongolia. The name is due to the fact

that a part of this road leads along the river Chuya, a tributary of

the Katun. The route was originally created in the 18th century by Russian

merchants who were trading with the people of the Altai and Mongolia

and somehow had to find a way to transport their goods to these remote

areas. In those times the road was nothing but a trail and it took ages

to get from Biisk and other regions north of the Altai to Kosh-Agach

where some kind of settlement, consisting mainly of storage huts, was

established in the first half of the 19th century.

A special difficulty presented the White

Ravine ("Belii Bom") between Inya and Chibit where the trail

was so narrow and dangerous that if someone wanted to cross it with

mules or on horseback he had first to walk through the ravine till the

other side and place his hat there so someone coming from the other

side could see that the trail was occupied and wait till the people

coming from the other side made their way through the ravine. Otherwise,

as it was impossible to make a turn on horseback inside the ravine,

one of the two parties would have inevitably fallen into the abyss.

The merchants trading on this route made considerable collective efforts to improve the route. They constructed a few road houses along the trail and supplied them. But the lack of means lead to the result that most projects for improvement remained mere theory. By 1901 another effort was made, by initiative of merchants from Biisk who collected 10.000 rubles and started to organize construction work on the route. In the end it took about 80.000 rubles to build a road that was finished in 1903 but almost didn’t deserve this name. It somehow eased transport and movement in comparison to former times but it could not be considered a reliable road at all, especially in autum and winter. Apart from that it it required great efforts for maintainment and as no one undertook them even the improvements that had been made from 1901-3 fell into decay. In 1914 a statal commission was deployed to the Altai to undertake a new planning for the construction of a stable road but their work was interrupted by World War I. Only after the revolution construction works started, some bridges and ferries were built and the old route was improved.

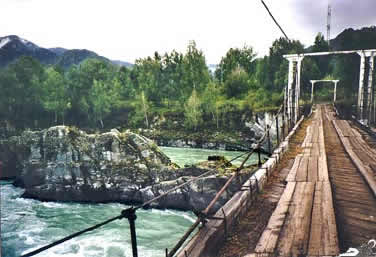

In the 30-ies construction works started

with the deployment of lots of deported people, prisoners of the concentration

camps that were constructed for this special purpose throughout Altai.

Therefore it can be said that the Chuiski Trakt in it’s nowadays

shape is a result of the GULAG system. With the employment of this non

voluntary workforce numerous wooden bridges were built in 1934 and 1935.

In 1934 for the first time some cars and lorrys made their way from

Biisk to Kosh-Agach. The journey lasted 5 days. Finally in 1936 in Inya

a hanging bridge was finished that led across the Chuya.

After World War II a lot of reconstruction was made and the old wooden bridges as well as the hanging bridge in Inya were replaced by bridges from iron and concrete. The road is good now and comparatively well maintained and still the most important road in Altai, though traffic on it is scarce. It serves as a means to transport fuel to Altaian villages and to Mongolia, furthermore trucks take second hand furniture from Russia to Mongolia. And the merchants from Biisk and other towns in the Altaiskii Krai are here again, supplying Altai with goods that are not produced here any more.

The rivers of the Altai are popular with

rafters. The Russian style rafting is done with catamarans which the

people disassemble and carry on their backs through the woods until

they get to the place in the river from where they want to start downstream.

There they put them together, inflate the floats and off they go.

(Photographs from 2000. Report written in 2003) |